2020 Update

2019 In Review

So we have 2017 that was one of the best seasons in recent memory, 2018 being average, 2019 was....

pretty good actually. Not quite the heights of 2017, but ticked a lot of the boxes: a reasonable proportion of good match-ups, upsets, smaller margins, and comebacks.

In 2019, the points difference between teams was 10.8 on average, ranked 34th over all 123 seasons. Not too shabby (2017 was ranked 13th in comparison with a mean difference of 9.1).

Figure 1: Recent distribution of difference in points between the home team and away team prior to the match. The first quarter of the season is excluded to allow enough time for the competition to settle.

Round by round, we see below that there was a reasonable set of match-ups each week, the exceptions being round 20 and 21. Round 20 had these delightful fixtures:

GWS vs Syd (5th vs 15th)

Fre vs Geel (11th vs 1st)

Melb vs Rich (17th vs 4th)

Adel vs StK (8th vs 14th)

Coll vs GC (6th vs 18th)

Carl vs WC (16th vs 2nd)

Bris vs WB (3rd vs 10th)

Figure 2: Mean difference in points each round. The first quarter of the season is excluded to allow enough time for the competition to settle.

We had 20 blockbusters in 2019, instances of two top 8 teams playing each other separated by no more than 2.5 wins. This was 5 matches less than 2018 but we had 5 blockbusters on a Friday night so perhaps it felt like there were more (there were only 2 Friday night blockbusters in 2018). 2019 also only had one weak Friday night match-up, Hawthorn vs Collingwood in Round 16 (13th vs 3rd). Despite the prospects of a poor contest, Hawthorn ended up winning 4 points

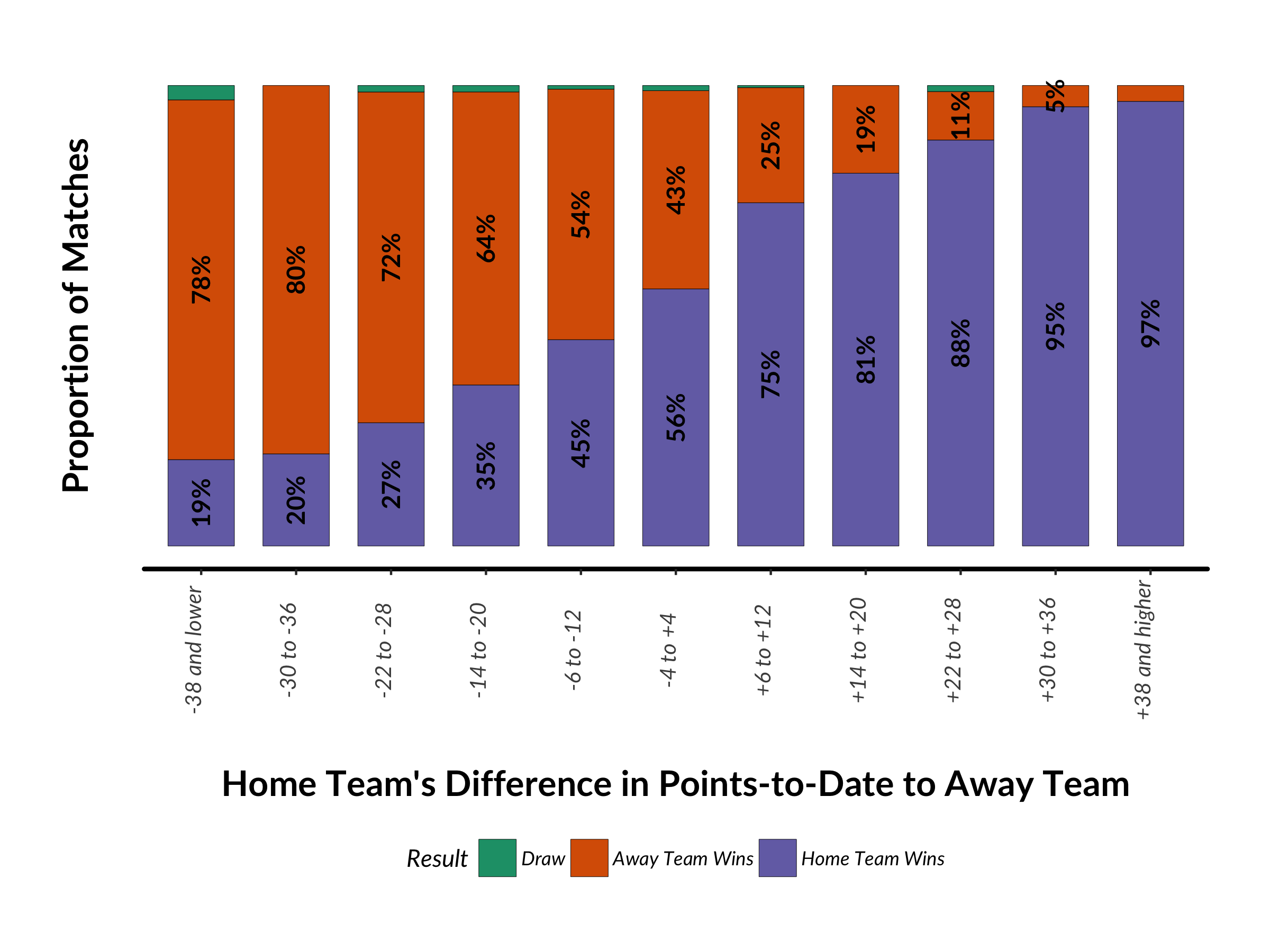

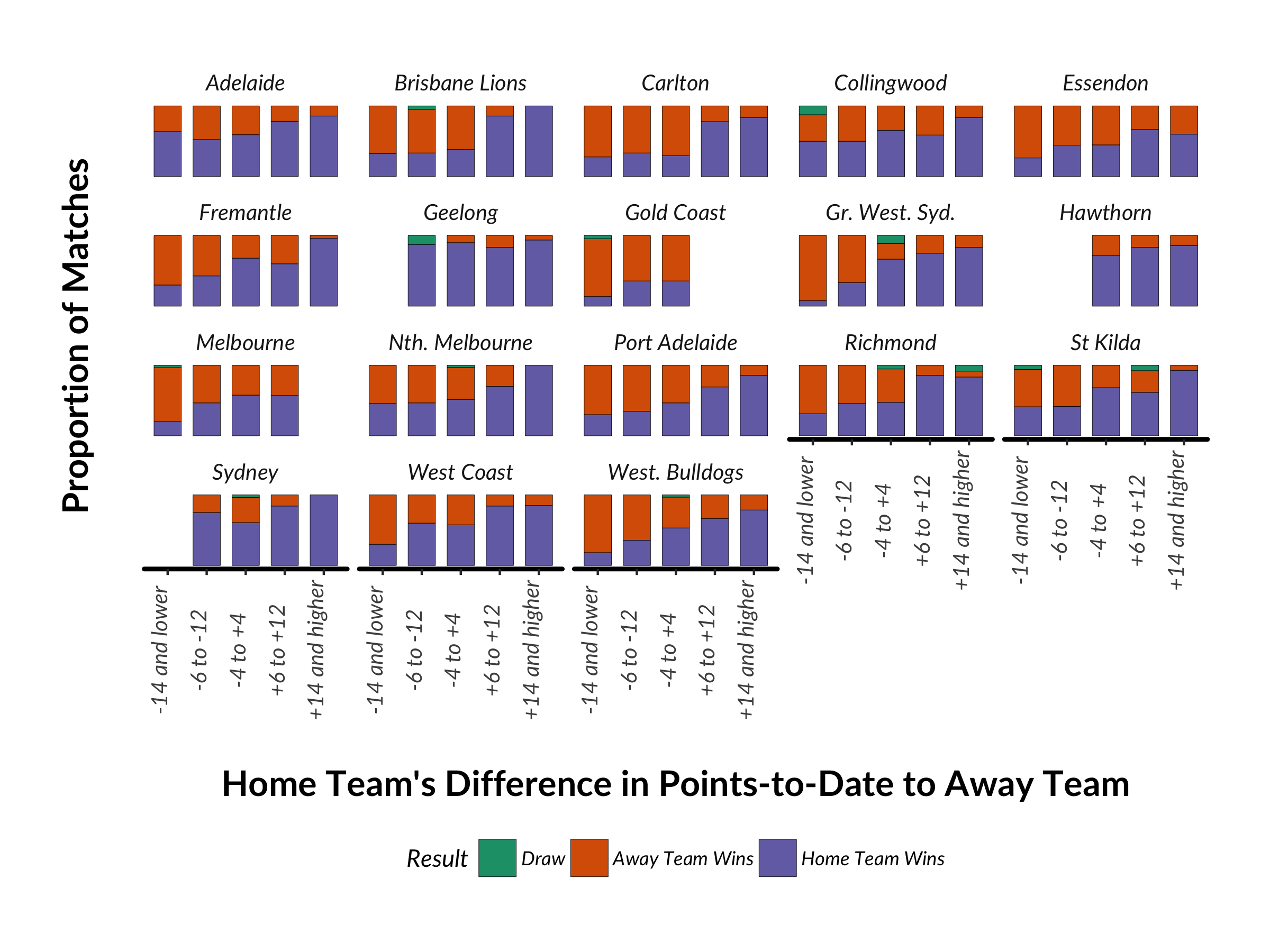

Speaking of upsets, this is another good measure of the quality of a season. One definition is when the home team gets up despite having 3.5 wins or greater to date LESS than the visiting team. This situation occurred 25 times in 2019, and the home team got up 9 times (36% vs 21% in 2018). Remember these?

Freo (12th) defeated Geelong (1st) in Round 20 by 34 points at Perth Stadium

The Bulldogs (13th) defeated Geelong (1st) in Round 16 by 16 points at Docklands

Carlton (18th) defeated Brisbane (5th) in Round 12 by 15 points at Docklands

With form like that, no wonder the Cats couldn’t get the job done when it counted in the finals.

The flip-side is where the away team gets up despite the home team having 3.5 wins or more greater than them. This situation occurred 23 times in 2019, with 5 upsets (a 23% upset rate, only bettered 20 times in history). Remember these?

Hawthorn (11th) defeat Geelong (1st) in Round 18 by 24 points at the MCG

Hawthorn (9th) defeat West Coast (3rd) in Round 23 by 38 points at Perth Stadium

Carlton (18th) defeat Freo (8th) in Round 15 by 4 points at Perth Stadium

North (13th) defeat Collingwood (2nd) in Round 15 by 44 points at Docklands

2019 also had one of the highest incidences of comebacks, where one team is behind at every change except the last or where a large deficit at 3/4 time was overcome). It was on par with 2017 (and 16th best of all time) with 11% of matches having large turns of fortune. Here were the highlights:

Doggies are down by 30 points at 3/4 time vs Hawthorn @ MCG then go on to win by 19

Hawks down by 31 points at half-time vs Carl @ York Park then go on to win by 5 points

Adelaide is down by 25 points at half-time and 16 points at 3/4 time vs Melbourne @ Marrara Oval; they go on to win by 2 points

GWS are down by 21 points at half-time vs Geelong @ Kardinia Park; they go on to win by 4 points

Carlton are down by 29 points at qtr time vs Fremantle @ Perth Stadium then go on to win by 4 points

And, finally, the per season mean and median winning margin decreased again, to levels not seen since the 1970s. Despite my team, Melbourne, having a shocker, 2019 was a competition showing signs of good health.

Figure 3: Mean and median winning margins per season.

So if it was so good, how did it translate into match attendance? Well, it was quite a mixed bag and followed club fortunes as a (very) general rule. Carlton fans started to to turn up again, averaging 47k while Melbourne's gains of prior years were lost, only averaging 29k, a level last seen in 2015. Disappointingly for the AFL, Gold Coast had fewer fans turn up than last year but perhaps they switched to Brisbane, up 34% to an average of 25k, a level not seen since 2010.

Figure 4: Year-on-year change in home team attendance.

Improvements in Predicting Match Attendance

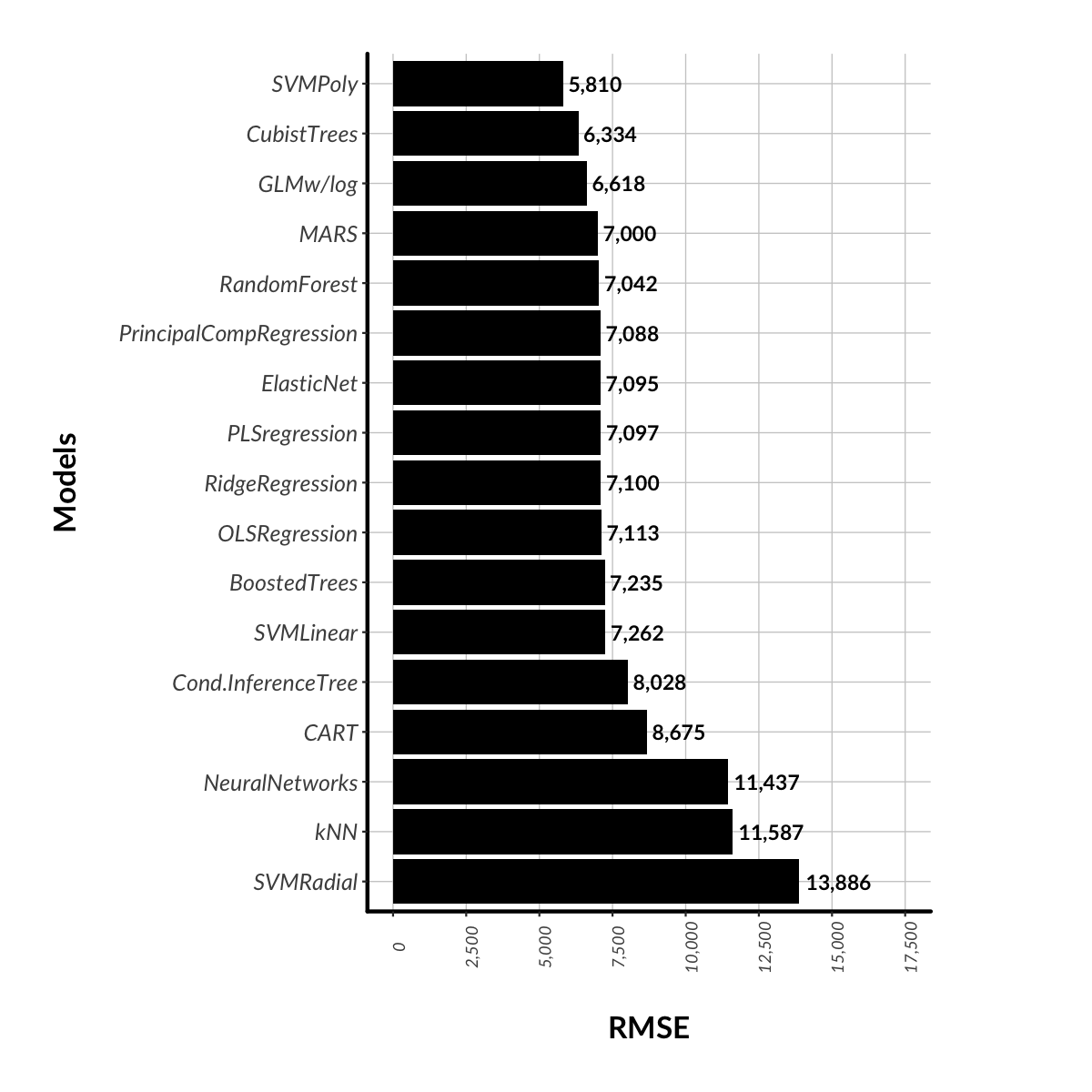

Once again, I am trying to hone my predictive model for match attendance. As expected (and nice to see), adding an additional season’s data has not yielded an improvement in RMSE (5,242 with the SVM Polynomial algorithm). As a reminder, RMSE means root mean square error, basically the average error of the model, that, on average, the model either under or over predicts match attendance by about 5,200 people each match. So, what’s left to try?

One trick up my sleeve is to trial an algorithm that is commonly the best performing algorithm at my work, XGBoost. XGBoost is the Porsche of Gradient Boosted Machines, a very powerful engine with a lot of options for the modeler to find the very best fitting model. In the end, it was good but no better than what I already had (RMSE of 5,254).

Looking at where my current best model had the largest error, it occurred to me that I had not really captured the phenomenon of match-ups between teams either in the top 4 or top 10. Particularly, near the end of the seasons, these matchups can produce larger crowd than otherwise be expected (and conversely for non top 10 match ups). For example, Richmond vs Brisbane at the MCG brought 76,995 in the final round of 2019, when they were placed 4th and 1st on the ladder respectively. Implementing this brought down my RMSE to 5,159, a nice little improvement.

I also added Season into the model as a numeric attribute. The thought is that perhaps there as something trend-wise that the model could pick-up, maybe something like a trend away from home state derbies drawing above-average crowds relative to non-derbies. Whatever the reason, this had a large impact with RMSE coming down to 4,845. Not bad but still nowhere near my target error of 3,000. Any further ideas on attributes that might help to correct prediction error are most welcome!

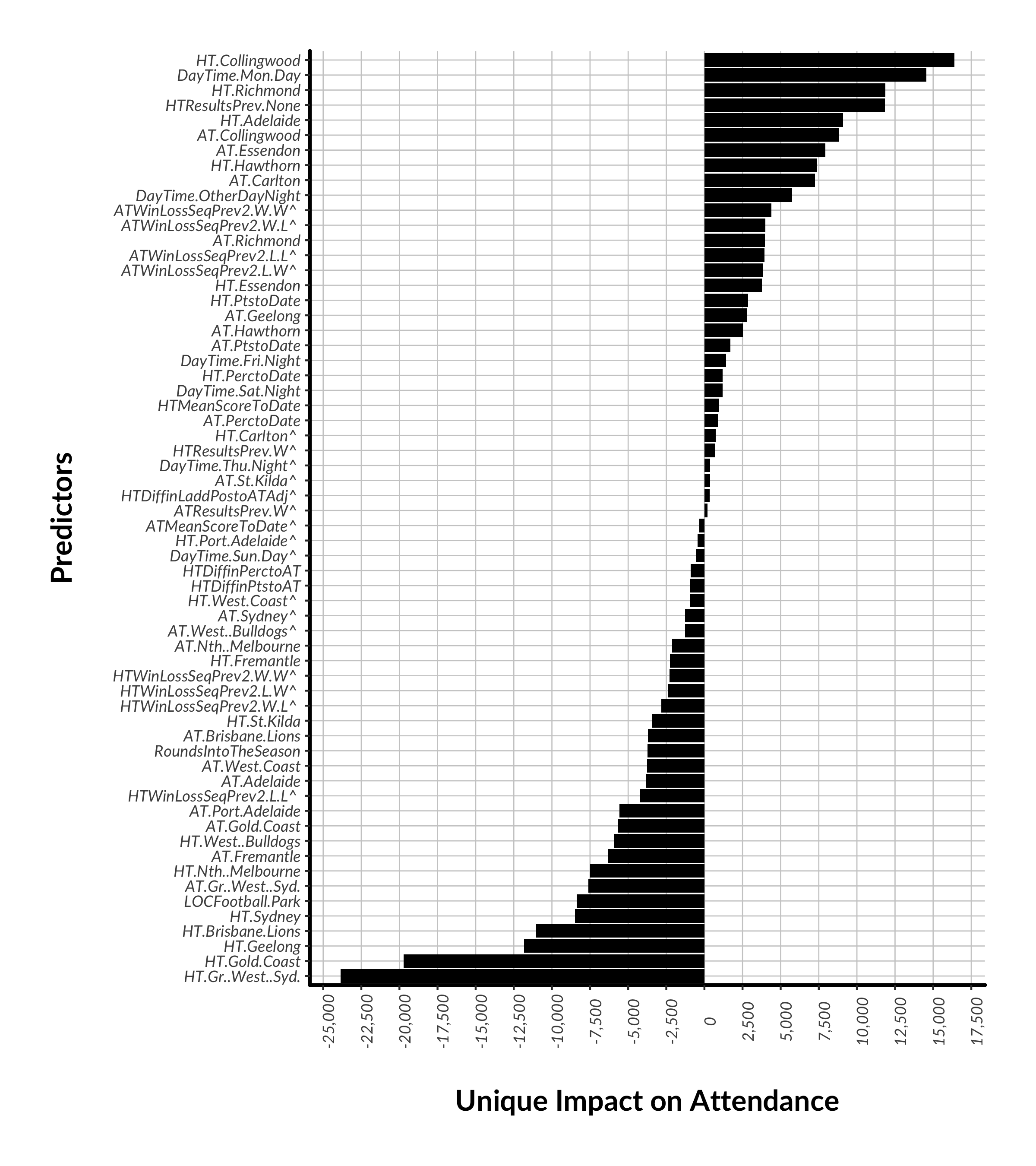

Here is the latest ranking of attribute importance for the SVM algorithm. A predictor is “important” if toggling between the attribute’s values increases the model error. If there are large swings in error, we can infer that the model relies on the attribute for prediction. We see below that there are few predictors that have a large impact on explaining attendance, while most predictors are adding “tweaks”.

Figure 5. Attribute importance in the final 2019 SVM algorithm. The value of the x-axis is an average ratio of error when values of that attributes are put through the model relative to the baseline error of the model. Therefore, attribute with importance values close to 1 mean that on their own they have minimal marginal impact. In addition, be careful when interpreting the above predictors. For example, LOCFootballPark does not mean that matches at Football Park had large attendance. It means that it had a large impact, either positive or negative. And in this case, we can assume negative since when this predictor is set to zero, we are essentially talking about matches being played at the Adelaide Oval, a venue with higher capacity.